When my teacher Pamela Boyce Simms gave a presentation at the 2017 ISE Summer Gathering in Marshfield, she opened with the intentionally inflammatory statement that “It’s all the fault of the Enlightenment.” An audible gasp arose from the audience, a moment of silence before hands shot up to defend a cornerstone of Bookchin’s emphasis on the primacy of rational thought and scientific analysis over mysticism and religious doctrine, which he argued are mutually irreconcilable. This essay represents my attempt to reconcile and hopefully shed light on the tension between the practice of spiritual inquiry and inner development within the practice of social ecology.

Before joining the ISE faculty to co-teach the Bioregional Agriculture course in the 1986 summer program I was an organizer for NOFA (Northeast Organic Farming Association). With my newly minted Masters in Extension Education, I was finally realizing my dream of becoming a market gardener and organic advocate. I had attended a couple of ISE workshops at Cate Farm in the seventies, but knew little about Social Ecology and what it meant. In the course of organizing the 1983 NOFA Summer Conference I was introduced to Murray Bookchin, who was invited to be our keynote speaker. His talk, later published in The Modern Crisis as “Market Economy or Moral Economy,” had resonated strongly with me. Although summer was a very busy time, on days when I traveled to Waitsfield, VT for my classes I immersed myself as much as possible in the rich discussions and presentations by an array of speakers, highlighted by Murray’s electrifying lectures.

Bookchin’s passion and erudition galvanized my intuitive understanding of the radical social and political change needed for a paradigm shift towards ecological awareness in the realm of food and agriculture. I already believed that ecologizing and relocalizing the food system could be a key fulcrum for a wider transformation towards democratic community control of essential human needs. As the ecological degradation of soil, water, and biodiversity continued to accelerate under the corporate agri-industrial mass food system, directly damaging human health in the process, I saw the potential of the organic movement to lead this transformation.

The reharmonization of humanity and nature, along with the concept of human civilization as second nature that has evolved from and remains part of the non-human first nature, was among the more compelling ideas that cemented my adoption of social ecology and the ISE as my intellectual home. The emerging ecological paradigm, as I conceived of and studied it, went beyond reductionist science and analytical methods to emphasize the evolutionary benefit of collaboration rather than the Social Darwinist model of competition and “survival of the fittest” as the primary driver of evolution. I was jazzed by the holistic insights that connected health, soil, plants, animals, and the complex interplay of human cultures that co-create biologically rich, fecund ecosystems.

The core understanding that humans are as much a part of nature as earthworms drew my mind to the controversies raging in the organic community in the 1980s. In particular, I was trying to deconstruct the notion that the synthetic origin of materials used to fertilize the soil and control pests was the key determining factor that distinguishes “natural” organic purity from “chemical” agriculture. For many of my colleagues this distinction represented a “clear bright line,” easily communicated to consumers in the burgeoning but still tiny organic marketplace. However, this had always seemed to me like a message that humanity was not part of nature, and thus anything altered by human ingenuity was suspect and ultimately “unnatural.” Though most agreed that the distinction between “synthetic” versus “natural” was not ecologically meaningful, the capitalist marketplace demanded such oversimplified communication to assure consumers that their food did not harbor impure synthetic chemicals.

My exposure to ISE teachers such as neo-pagan activist and journalist Margot Adler, Haudenosaunee leader John Mohawk, Ynestra King, organizer of the Women and Life on Earth Conference, and one of my first inspirations, eco-designer and New Alchemy founder John Todd (along with his spouse, Nancy Jack Todd) confirmed my sense that this community was indeed on my wavelength. However I was also surprised by discussions that seemed to reject any role for spiritual inquiry or inner development work within social ecology programs. The critique of superficial New Age dabblers in mysticism made sense to me, to say nothing of my repugnance for those that sought to cash in on this trend. But I had also learned enough about larger truths common to many ancient traditions and indigenous cultures to understand that these universal insights and values, including the sense of kinship with all of nature, was important to cultivating the kind of ethical framework espoused by social ecology.

Though I shared the common disdain for organized religion and its associated dogma and patriarchal hierarchy, I was quite perplexed by condemnations of any form of spiritual practice, such as the various schools of Buddhism that offered non-theistic and social justice oriented teachings that seemed highly compatible with the social ecology sensibility. It seemed that Bookchin relegated any interest in eastern philosophy to the realm of irrational mysticism, “a night when all cows are black” as he was fond of quoting Hegel. His dismissal of any interest in eastern philosophies has also been pointed to as an indication of his Eurocentrism.

Bookchin’s tendency to resort to name-calling and otherwise mocking those who disagreed with him is exemplified in a lengthy diatribe railing against John Clark for personal attacks, in which he also dismisses all of Buddhist philosophy based on a reading of Nagarjuna.1 Whether or not his accusations leveled against Clark are justified, Bookchin’s use of his philosophical disagreements to characterize all of Buddhist philosophy as irrational demonstrates his inability to acknowledge anything beyond the dualistic “either/or” kind of thinking that is so corrosive of organizational relationship-building. In his conclusion Bookchin expresses this starkly in saying,

“In sum, my confrontation with Clark is a confrontation between the Enlightenment and the counter-Enlightenment, rationality and irrationality, secularism and mysticism (if not an emerging religion), activism and quietism, innovation and adaptation, and, most basically, the revolutionary tradition and the reformist tradition.”

With a similar level of dismissiveness, Janet Biehl’s takedown of feminist spirituality in her essay entitled “Politics of Myth” exemplifies the conflation of the non-rational with the irrational in saying, “The politics of myth is based on an appeal to our intuitions and emotions…These aspects of ourselves are incapable of distinguishing between symbol and symbolized, between dream and reality, between appearance and the authentic world–both natural and social.”2

This kind of “either-or” thinking that sets up false dichotomies, devalues the feeling-intuitive aspect of our full selves, and reduces reflection on archetypal symbols to “worship” seemed to be all too common within the ISE (and perhaps the radical left in general). In the course of witnessing various conflicts and dramas within the community I was not alone in noticing an inability to listen to differing viewpoints, or to recognize and support diverse learning styles and emotional needs. The left’s tendencies towards factionalism, while decried in principle, seemed to permeate internal arguments, as people were sometimes dismissed by labeling them as the wrong kind of “ist.” Intellect and reason, important as they surely are, seemed to be the only legitimate forms of expression, leaving concerns for inner development or exploration of non-rational forms of knowledge unaddressed. When questions about this dichotomy arose in a class with a guest speaker representing the American Friends Service Committee (a Quaker-affiliated peace activist group), I asked him whether he thought that spiritual development or political action was more important. In response he quoted our mutual friend, Dave Dellinger (well-known activist and one of the fabled Chicago Seven): “That’s like asking if it’s more important to breathe in or to breathe out.”

Students who expressed interest in spiritual questions got little support, though several produced top-notch work that used scholarly, intellectual discourse to argue for integrating these forms of non-rational knowledge into our teaching. Others, feeling belittled or ostracized, simply dropped out of the ISE community.

I found myself having to avoid talking about certain things, and reluctantly accepted that, while the ISE was my intellectual home, it fell short of meeting my need for spiritual growth. That role was filled by the Shambhala Buddhist community. Having been exposed to these teachings soon after I became immersed in the culture of the ISE, it seemed that this philosophy served as a kind of antidote to some of what was causing me discomfort in my new intellectual milieu. As I explained in my book Organic Revolutionary:

The foundation of the Shambhala teachings is one of “basic goodness,” a simple but profound understanding of human nature that recognizes the potential for any of us to wake up. In contrast to the widely held notion amongst western religions that humans are inherently sinful and must be taught to behave ethically (often via some form of coercion or threat of punishment), this view holds that we are all born with a natural worthiness as human beings. … These teachings offer a non-religious and nontheistic approach to making friends with one’s own mind, utterly without requirements to obey a leader, pledge loyalty to a religious scripture, or join an exclusive club.3

In comparing social ecology to Shambhala Buddhism I wrote:

I have never found any inherent contradiction between what the two disciplines teach, and consider them to be complementary and equally valid schools of thought. The concept of basic goodness in particular points directly to the pursuit of social justice as a fundamental prerequisite for an enlightened society. It also provides an explicit framework for caring for nature as well as other humans. This is comparable to the social ecology world view—that humans are not separate from nature, and that human activities are not inherently destructive or antithetical to an idealized pristine nature.4

More recently I’ve also learned that other ISE colleagues and friends who have adopted deeply spiritual journeys have also found it best to avoid discussing this aspect of their lives within the social ecology community. It was only when reading Beverly Naidus’ moving reflections on the life of her dying husband, Bob Spivey, that I even knew of their Buddhist engagement, or that Bob had lived as a Zen monk for a time. Beverly’s powerful writing in her Substack memoir “Gravity Humming” continues to move me in admiration of their common devotion to the project of social ecology, teaching, activist art, scholarly study, health care, compassionate community building, and so much more.5

Lessons from the organic front

As chronicled in Organic Revolutionary, some of the lessons learned from my organizing work in the organic community convinced me that “the greatest obstacles to our cause were an egocentric lack of empathy and compassion, a dash of self-righteous arrogance, and a tendency to demonize the opposition often evidenced in our leaders.” This weakness is common to many movements, and is not unique to the left. Some of the lessons learned in the course of working inside the US Department of Agriculture and collaborating with “the enemy” to institutionalize organic in the 1990s were painful ones, as few of my colleagues and comrades understood the revolutionary potential of what I was trying to do. Activists whom I had respected shunned me, one going so far as to contact Murray and insist that he fire me from the ISE Goddard faculty, after having grossly distorted what I had told him in an interview. However, I did find support among most of our students and fellow faculty members, despite some misgivings and even hostility from others.

There were certainly times when I considered leaving the ISE in frustration, but chose to persevere in the face of the personal challenges because of the enormous value I placed on the insights of social ecology for addressing the looming world crises we could see were on the horizon. I also believed that by persisting in contributing to the project of social ecology, especially after losing our land base and academic affiliation with Goddard, my perspective would help maintain the ISE’s historical connection to building practical skills and knowledge in alternative technologies and care for the earth, which was in danger of disappearing entirely in favor of purely intellectual programming. In subsequent years the opportunity to collaborate with colleagues and friends like Bob Spivey, who attempted an ambitious social ecology eco-restoration and education project in the Pacific Northwest called SEEDS, and Brian Tokar, who now co-teaches the Food & Climate Justice course with me, solidified my commitment to the utopian vision that had guided me through so much internal struggle.6

Envisioning the future as systems collapse

I was fortunate to connect with Pamela Boyce Simms as a spiritual teacher who identifies herself as an “evolutionary culture designer” sometime in 2016. Her purpose of supporting activists in co-creating the “joyous, resilient remnants” of humanity in the coming time of extreme disruption has spawned a movement called “Community Supported Enlightenment” (CSE). The irony of her opening remark that sparked such outrage at the ISE gathering is not lost on me. Of course we must understand the mixed legacy of the Enlightenment, which has contributed to cultural evolution in a fundamental way. However this spark has also led to the devaluation of non-rational ways of knowing, spiritual and intuitive understanding, and other belief systems that created the split of humanity from nature with its associated human and ecological devastation. It should be a given that some balance is needed.

Pamela’s work combines teachings from Buddhist, Quaker, and other esoteric wisdom traditions, as well as an eclectic mix of neuroscience, quantum physics, and Jungian therapy. Her focus is now on service to the marginalized and distressed community of the African diaspora—of which she is a member—through herbal medicine, wellness programs, and nutritious food. Her international network of trainees and practitioners is learning to support work towards building bridges between this community and the economically marginalized and distressed white Appalachian community that struggles with opioid addiction through mutual aid, herbal medicine and food production.

The training offered through the CSE network focuses on inner development practices based on ancient spiritual traditions to prepare us to navigate the cataclysmic social, political, and ecological upheavals we are now experiencing. It is this inner work that has allowed me to persevere in swimming against the current and speaking my own truth, despite these conflicts, both personal and political, within the social ecology milieu. There is no preaching of religious dogma, allegiance to a guru, or hierarchy. Though Pamela is the founder, primary teacher and convener of this project, she does not hold power in the sense of demanding participation in particular activities or any form of coercion. There is no fee for participation, but those who are able may donate to the non-profit entity she set up to provide service to her community. Pamela is a Buddhist monastic and renunciate who does not receive any compensation for this work aside from basic living expenses (though she does work with some private clients as a therapist/counselor).

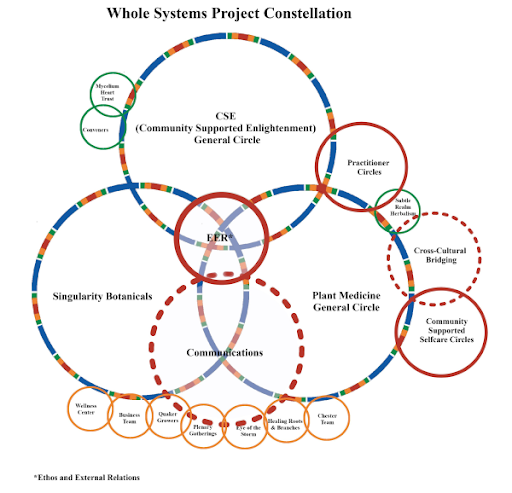

Sociocratic governance is central to the CSE constellation, with its organizational chart composed of interlinking circles resembling a bubble map (image below). Sociocracy is a Quaker-inspired organizational model originally developed by co-housing community organizers. The Sociocracy for All website states, “We believe the best decisions are made when everyone’s voice is heard, that’s why we use sociocracy to save time, make inclusive decisions and create more human organizations.” There are other similar decision-making models, but this is one that I have learned really works when everyone involved is on board with the basic intent of truly democratic management and shared leadership. Deliberations and proposals are developed in rounds, giving each participant the opportunity to express their own thoughts on the topic. Rather than striving for consensus on a proposal with an up-or-down vote, participants indicate their consent, meaning “good enough to try.” If anyone cannot consent it indicates a need for more refinement of the proposal. The conversation continues around the circle until a proposal is shaped that everyone thinks is good enough to try, with the agreement that it will be revisited and adjusted as needed within a set time frame. If consent does not come within the necessary time frame, an ad hoc person or team may be tasked with gathering more information and returning with proposed refinements that can be made. This system requires a strong intention to practice the skills of deep listening, learning to set aside ego-supporting needs for affirmation while respecting all voices.

This method of ensuring that all voices are heard and that all participants can live with any decisions made avoids the pitfalls of both the “either/or” majority rule decision-making preferred by Bookchin, as well as the consensus model, which allows a single individual or small faction to stand in the way of a proposal that everyone else agrees with.

The path forward

My personal ongoing quest is to keep strengthening the inner resources needed to continue working towards “the world we deserve.” This determination was affirmed in the course of helping organize the week-long Ecosocialism from Below gathering in Marshfield in the Summer of 2022. This gave me the opportunity to work with the key players of Cooperation Vermont, who had recently purchased a struggling local country store and were running it as a worker-owned collective. This community-building project has quickly turned into a key resource hub for critical mutual aid and relief during the devastating floods that hit Vermont in July of 2023. Having developed a concept paper to outline my vision of creating a community land trust for people like me—“aging hippies with land,” as one observer put it—that was circulated during the Ecosocialism from Below event, I found like-minded colleagues, comrades, and friends who enthusiastically embraced the concept. Together we have now established the Cooperation Vermont Community Land Trust, and are getting ready to implement our first transfer of land that will be removed forever from the market economy. This is one step towards rebuilding local economic cooperation, recommoning the essential necessities of life that are our birthright as humans. We have deliberately embedded the principles of Sociocracy into our by-laws, as the governing structure of the new organization.

As this year of horrendous wars, environmental upheavals, expanding fear, instability, and associated rise of fascist ideologies comes to an end, the ethical framework and the decentralized, bottom-up political vision espoused by social ecology is needed more than ever.7 If the ISE is to thrive and continue attracting younger generations of leaders and activists my fondest hope is that it will become more inclusive and collaborative by practicing the skills of democratic, egalitarian governance. This includes seeking a balance between rational/intellectual discourse and spiritual/personal development that values and respects “neurodiverse” learning styles and non-rational ways of knowing – as centered in most African American and indigenous cultures.

This message comes with gratitude for and inspiration from younger generations of spiritually and politically engaged activists who can carry on and implement the theories and new learnings to help build diverse local utopias that can serve as revolutionary lifeboats—or pirate ships, if you will—for the storms already upon us.

- Murray Bookchin, “Turning Up the Stones: A Reply to Clark’s October 13 Message.” http://pzacad.pitzer.edu/anarchist_archives/bookchin/turning.html.

- Janet Biehl, “The Politics of Myth,” Left Green Perspectives (No. 7, June 1988).

- Grace Gershuny, Organic Revolutionary: A Memoir of the Movement for Real Food, Planetary Healing, and Human Liberation (Montreal, Black Rose Books, 2020), 51-52.

- ibid 53-54.

- These writings are available here: https://beverlyenaidus.substack.com.

- This course is available here.

- Editors’ note: This essay was penned in December 2023.