“The fate of my grandparents’ neighborhood is grimly familiar to anyone who has spent time in a major American city. Despite more than half a century of civil rights activism and changing racial attitudes, American cities (particularly the old industrial centers of the Northeast and Midwest) remain deeply divided by race. Poverty rates among people of color in major American cities are staggeringly high. Vast tracts of urban land lie pockmarked with boarded-up buildings, abandoned houses, and rubble-strewn lots. At the same time, hundreds of thousands of acres of marshland, meadow, farm, and forest on the periphery of major metropolitan areas get gobbled up each year for vast tracts of new housing, shopping malls, and office parks.”

Thomas Sugrue, The Origins of the Urban Crisis: Race and Inequality in Postwar Detroit, preface to Princeton Classic Edition, xvii

“The problem of the Twentieth Century is the problem of the color line.”

W. E. B. Du Bois, The Souls of Black Folk

Though the “mainstream” environmentalist movement has been predominantly composed of white, middle-class progressives, there is an extensive history of working-class people of color organizing against environmental destruction as a direct threat to their health and safety. What we now call “the environmental justice movement” can be considered an extension of the long civil rights movement1 into matters of environmental protection and public health, first receiving national attention with the failed organizing campaign against toxic waste dumps in Warren County, North Carolina, in 1982.

Environmental justice is both a collection of movements of marginalized people fighting to protect their communities from environmental harm and a conceptual framework for understanding the sources and horrific consequences of such environmental violence against racialized peoples. It is to the intellectual and movement-building work of environmental justice that we owe such essential concepts as “environmental racism” and “climate justice,” which continue to shape ecological struggle. This has been particularly important for the development of movements against climate change. The climate justice movement, when it understands itself as such, has integrated a racial justice framework, with the recognition that neither the blame for nor the consequences of climate change are equally distributed, the bulk of responsibility for the crisis falling heavily on Europe and its settler colonies and the bulk of suffering as a result borne by colonized peoples across the global South.2 This matters not just as a source of moral urgency, but as a starting point for any serious solutions to the crisis, which will necessarily rest on political commitments to anti-imperialism, colonial reparations, and indigenous sovereignty.

In short, the basic insight of environmental justice—that environmental devastation is carried out to racist effect, through the same inequalities that create a racist society—is essential for making sense of and responding to the general social crisis in the twenty-first century.

I wish to suggest a further layer to the intellectual work underlying environmental justice. Rather than elaborate on the many ways that ecological devastation has racist effects, I will instead invert this, and explore some of the ways that racism has catastrophic ecological effects, using as a case study the central role of anti-Black racism in the suburbanization of American cities in the mid-twentieth century. This is an area where social ecology can make an important theoretical intervention in how we think about environmental justice, with social ecology’s understanding of environmental destruction emerging from social hierarchies such as racism. This essential insight of social ecology allows us to reconceptualize anti-racism as a necessary foundation of any ecological politics.

Additionally, there has so far been minimal theoretical work undertaken to understand racism within the framework of social ecology. While social ecology has laid essential theoretical groundwork for a revolutionary politics that goes beyond class, and for appreciating racism as a system of hierarchy that is not simply an appendage to the class system, only rarely have social ecologists given it particular intellectual focus. More often, “racism” and “white supremacy” are merely referred to within the long litany of hierarchies that plague our society: ableism, transphobia, homophobia, colonialism, etc., all to be recognized and overcome but also all too often submerged into the generalizable principle of anti-hierarchy. This has not been the case with, for instance, patriarchy or antisemitism, which social ecologists have sought to analyze in great detail as distinct forces of domination through their published works. It is my hope to help end this intellectual neglect and extend to racism—and more specifically anti-Black racism in the United States—the same focused treatment. I also wish to encourage social ecologists to grasp more critically the merits and pitfalls of local democratic autonomy in a profoundly racist society. I have written more of this danger of “dark municipalism” elsewhere,3 and intend to revisit it in greater detail in the future. We need to better understand the history and mechanisms of racial segregation to effectively grasp these threats latent within localist politics.

To make this case—that racism has constituted an ecological force in American history—I will begin by explaining the foundations of urban segregation in the first half of the twentieth century. Then, I will discuss how this segregation was challenged and shaken by the continuing northward movement of Black migrants and the civil rights movement, leading affluent whites to reimagine what separation from Black people could look like and embark on an immense project of defensive retreat from everywhere that Black people had advanced in their struggle for freedom. Lastly, I will attempt to assess the nigh incalculable scale of ecological destruction that resulted from this retreat: a retreat not just from cities, but from the public sphere as a basis of collective life, and from the very idea of a commons. The forces of white supremacy have played a powerful role in building American society into this cancerous beast shredding the ecological conditions of its own existence. From here, we can look to new terrains of social struggle that attack the material foundations of anti-Black racism in the United States—tenant rights, public housing, public transportation, police and prison abolition, reparations, and creation of expansive urban commons—as strategic fronts in the fight for an ecological society.

* * *

“Segregation” is commonly imagined as a Southern problem. The prevailing story of the civil rights movement revolves around bus boycotts, lunch counter sit-ins, and voting rights in the South, and understandably so; these are the areas where the civil rights movement was most successful. The social caste system governing interpersonal relations between Blacks and whites during this apartheid era in the American South has been largely demolished. Unfortunately, triumphalist narratives of the civil rights movement sit atop the persistent reality of segregation across the entire country, a legacy of that movement’s failure to overcome those aspects of the American caste system that were not limited to the South. Segregation is a structural feature of American life in every single city and region where Black people live in any numbers, and simply cannot be understood as just “a Southern problem.” This history will attempt to lay bare how segregation has managed to persist, and even harden, many decades since its supposed defeat in the 1960s.

Flight to Freedom

While there were of course Black communities in nearly every major city at the dawn of the twentieth century, the overwhelming majority of the Black population remained concentrated in the territory that had been a part of the Confederacy.

Despite slavery’s formal abolition after the Civil War, involuntary servitude persisted in several forms. Plans for land reform to redistribute the enormous plantations to freed slaves during Reconstruction were never fully carried out, and most Black people were landless workers who remained bound to the white planter class (oftentimes literally their former masters) by debt peonage in a tenancy system called sharecropping. The parallel failure to defend the Reconstruction governments of the South resulted in the armed reconquest of political supremacy by the white power structure. This restored planter elite constructed another system of forced labor by way of mass imprisonment, with Black prisoners put to work on “chain gangs” for public projects or allocated for private use via “convict leasing.” The political economy of the South during this period could therefore be considered a sort of racial serfdom that was nestled within the wider “free labor” market system. At its core, this caste system revolved around maintaining a fully subordinated laboring class of Black farmworkers, but it also governed every aspect of social relations, with ironclad expectations of interpersonal deference by Black people of all ages, sexes, and classes to whites and taboos against any form of “social intimacy” between the races.4

During World War I, a trickle of Black people from the South migrated out of the region, mostly to cities with new wartime opportunities for employment. Labor recruiters from the North circulated leaflets offering jobs to any who would come north. After the wartime boom subsided, most observers expected these migrations to end, or even to reverse. But instead, the trickle only swelled.

In the 1920s, the economy of the agrarian South was contracting. Cotton and tobacco prices had collapsed, and the boll weevil bedeviled Black cultivators across the region. Black people were further subjected to a new wave of white supremacist terrorist violence. The first Ku Klux Klan had largely disbanded after Congress’s passage of the Enforcement Act in 1871, which empowered the president to arrest members of white supremacist organizations without charges. However, the 1915 film The Birth of a Nation, based on Thomas Dixon, Jr.’s novel and play The Clansmen, inspired white supremacists to re-found the Klan. A lynch mob in Georgia abducted a Jewish man from his prison cell and murdered him, before setting a cross ablaze and declaring their rebirth as the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan.5 The second Klan quickly spread, and with them a surge of lynchings.

The regional bloc of the Southern Democratic Party was ruled as a single-party apartheid state, maintained over decades through an authoritarian cocktail of sham elections, disenfranchisement of Black people, and paramilitary terrorist violence. Many now having relatives or contacts living in cities outside the South, more and more Black people uprooted themselves in a flight to freedom. Often making travel plans in secret to avoid retaliation, Black people eventually numbering in the millions made these daunting, risky journeys. The severe labor shortages in industrial cities during World War II brought on the greatest influx of Black migrants. But even after the war, when industrial jobs for Black workers became scarce, this escape from the South continued. All in all, the Great Migration (as this mass movement of people is now called) involved 6 million Black people leaving their homes in the South between 1915 and 1970.6

These refugees from terror and tyranny sought to leave behind white violence and their subordinated caste position within the economic order. They were unfortunately to discover that these were also realities in the industrial cities of the North, albeit in a different form. Having escaped Jim Crow, Black arrivals found themselves facing what some of them humorously called “James Crow”—the system of white supremacy governing Northern and Western cities that was Jim Crow’s more respectable cousin.7

Meeting James Crow

The era of the Great Migration was shaped by an intense process of urbanization and industrialization in the North. Immigrants from around the world, displaced farmworkers, and Black refugees from the South flooded into cities like New York, Chicago, Los Angeles, and Detroit in search of industrial employment. These cities were bursting at the seams, and new private sector housing construction was unable to keep up with population growth. Tenements were subdivided and sublet in an endless quest to fit more people into existing urban housing, with workers sometimes sleeping in shifts.

The New Deal political coalition responded to this failure of the private housing market by financing an enormous wave of public housing development. The primary goal of these projects was not to provide housing to poor people who cannot afford what is available on the market (i.e., social welfare spending, as public housing is typically thought of today), but rather to overcome the incredible shortages of housing that were affecting people across lines of race and class.

But despite the immense power of the New Deal coalition in Congress, it was a precarious one. Northern liberal Democrats, generally supportive of civil rights, needed the votes of ardently segregationist Southern Democrats. The New Deal project was dependent on the apartheid regime of the Southern states as a core part of its coalition, and as such could pass little that challenged the racial caste structure of the country.

The political battles over federal public housing legislation illustrate this well. When President Truman tried to pass the Housing Act of 1949, anti-New Deal conservative Republicans in Congress developed a clever strategy to kill the bill. They proposed a “poison pill” amendment to ban racial discrimination and segregation in the public housing program. These conservative Republicans were opposed to public housing on principle; they did not care in the slightest about whether it was segregated or not. Their goal was to split the coalition of Northern liberals and Southern Democrats by making the public housing legislation unpalatable to the latter.8

The Northern liberals in Congress were then left with a choice. They could support the amendment and uphold civil rights within the New Deal social-democratic framework and lose the votes of the Southern Democrats required for any such legislation to pass, or they could reject the amendment to preserve their coalition and enshrine segregation in federal housing policy. They chose the latter. And they made this choice again and again throughout the expansion of New Deal housing programs. Through this and many other pieces of legislation, the federal government took on an immense role in the creation of affordable housing for urban workers, and did so with the specific and explicit intent to keep Black people apart and in economic subordination.

With public housing, New Deal racism took a fairly basic form. Each new construction was designated for occupancy by a single race. This kind of top-down segregation was imposed even in places where rigid color lines had not previously existed, creating racial geographies that in many places endure to this day.9

The federal government’s racist role in subsidizing private housing was somewhat more complex—and more destructive. In essence, federal housing policy created the greatest wealth accumulation process for working-class people in American history while systematically excluding Black people from being among its beneficiaries, and wielded its position in the housing credit system to ensure that these communities be uncompromisingly segregated.

In 1933, Congress created the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) to refinance home mortgages that were in risk of default. They created a new kind of mortgage that ensured the homeowner was building equity through their monthly payments. These borrowers could then share in the appreciating value of their homes before owning them outright. As the HOLC expanded its pool of borrowers, they took aggressive steps to ensure a whites-only program. They created color-coded maps of every metropolitan area in the country that assessed the investment “risk” of every neighborhood. The main criteria for assessing this “risk” were the racial composition of a given neighborhood. Grade A (green) areas were described as new and “homogenous,” meaning inhabited solely by white, non-Jewish Americans. Grade B (blue) areas were those of older housing stock, but still of homogenous white occupancy. Grade C (yellow) areas were those “on the decline,” meaning that they were at risk for transitioning to Black occupancy, such as by bordering a Black neighborhood. Grade D (red) areas were those inhabited by Black people, no matter the housing stock or class composition of the neighborhood. Prospective borrowers had a strong chance of being approved if their home was in a green or blue area; they had little chance if it was a yellow area, and zero chance in red areas.10 This system of “risk assessment” is known as red-lining.

This served as the bedrock of subsequent federal housing policy. A year later, in 1934, Congress authorized the Federal Housing Administration (FHA), which insured mortgages for prospective homebuyers. Because banks shouldered less risk if a given borrower were to default, this dramatically expanded the pool of homebuyers who qualified for a mortgage. While expanding homeownership to millions of working-class people, the FHA put new restrictions in place to both exclude Black homebuyers and socially engineer segregation from the federal level. Using the HOLC’s color-coded maps, the FHA refused to insure mortgages in neighborhoods that were not whites-only. Furthermore, these insured mortgages could not be used to facilitate any home purchase that would desegregate a given neighborhood. They particularly favored areas with physical barriers separating white neighborhoods from Black ones, which were deemed to be at less risk of “infiltration of…lower class occupancy and inharmonious racial groups.”11 FHA assessors paid close attention to maintaining segregation of public schools, their official manual stating that if children “are compelled to attend school where the majority or a considerable number of the pupils represent a far lower level of society or an incompatible racial element, the neighborhood under consideration will prove far less stable and desirable,”12 as well as to future possibilities for the racial transition of neighborhoods, which was to be vigilantly avoided. As one housing expert put it in 1955, these federal housing agencies implemented “a racial policy that could well have been culled from the Nuremberg laws.”13

Wedded to this institutional racism was an anti-urban bias, with a strong bent towards insuring mortgages for new, low-density construction on the edges of urban areas. Federal housing policy as a direct subsidy for suburbanization exploded with the end of World War II and the return of American soldiers. It further helped ensure the absolute segregation of these new suburbs.

As a general rule, the guidelines for federally backed housing and transportation projects were handed down from federal agencies to be implemented by local officials. These local planners, along with other local forces (such as real estate interests) played a central role in the entrenchment and defense of segregation in cities in the North, which also needs to be examined closely.

The stories and histories of how these policies of racist social engineering by the federal government and other institutional forces of white supremacy transformed the conditions of the lives of real human beings in cities across the country, remaking each’s built environment and geography, could fill many thousands of pages. In order to provide a degree of grounding specificity, I will hone in on the city I know best: Detroit, Michigan. Detroit is not unique, and its case is simply an effective illustration of dynamics in motion nationally in the mid-twentieth century. The commonalities in these basic processes of historic transformation among even very different cities are unmistakable. I also wish to show in concrete historical terms how white supremacy was not (and is not) functioning merely as an ideological buttress to the class system, nor as a collection of transhistorical personal prejudices, but as an entire social order of racial domination drawing upon the expanding power of the state and materially entangled with all capital accumulation in real estate and housing. This history is necessary to understand how the process of class formation among the upper strata of workers and professionals into “the middle class”—homeowners with property interests wedded to capital despite their exploitation in the workplace—was inherently racial.

The process of retrenched segregation through suburbanization was gradual, and not easily defined by the mile markers of particular moments or events. Despite this complexity, I have broken this narrative into three eras to more easily understand it, each defined by the leadership of a white politician from Detroit who embodied the segregationist reaction of their time: Edward Jeffries, mayor of the City of Detroit from 1940 to 1948; Albert Cobo, mayor of the City of Detroit from 1950 to 1957; and L. Brooks Patterson, Oakland County prosecutor from 1973 to 1992 and Oakland County Executive from 1993 to 2019. Jeffries represents the era of upholding a reigning apartheid in the city of Detroit; Cobo the beginnings of a retreat to higher ground as cracks in the levees of the color line appeared; and Patterson the erection of a wall behind the white escapees to shield them from contact with Black people.

Each of these men were more or less the same in their principles and politics, all committed to the idea that whites could not be made to live alongside Blacks. As the Black population swelled and the march of civil rights advanced, however, each in turn innovated upon their predecessor to adaptively maintain racial segregation in metro Detroit, with progressively more disastrous ecological consequences.

“Mayor Jeffries is Against Mixed Housing”: Detroit in the 1940s

Edward Jeffries was a conservative Detroit City Council member, first elected mayor when he took on a weak incumbent embroiled in a major corruption scandal. In Jeffries’ 1945 re-election campaign, he faced off against the much more formidable United Auto Workers (UAW) vice president Richard Frankensteen, who stood with the UAW’s progressive position on civil rights and housing. Jeffries used the issue of race and housing as an effective wedge to separate the union leader from the white working-class majority of Detroit voters.

Jeffries and his supporters combined anti-Black racism with a re-emerging anti-communism to paint Frankensteen as a subversive “red” who supported “racial invasions” of white neighborhoods.14 Campaign posters declared “Mayor Jeffries is Against Mixed Housing.” One neighborhood newspaper, the Home Gazette, praised his administration’s Detroit Housing Commission for “its previous stand against attempts of Communist-inspired Negroes to penetrate white residential sections.”15 The re-election campaign even created fake leaflets pretending to be Frankensteen campaign materials directed to Black voters, which were distributed in white neighborhoods. These read, “NEGROES CAN LIVE ANYWHERE WITH FRANKENSTEEN MAYOR. NEGROES – DO YOUR DUTY NOV. 6.”16 Jeffries was comfortably re-elected.

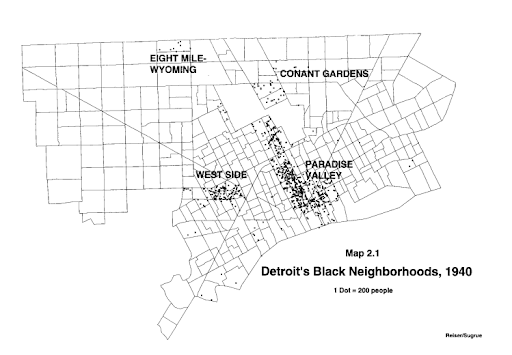

The mayor’s office held all sorts of direct and indirect influence over local housing policy, but he was never alone as an institutional defender of segregation. At this time, the color line in the City of Detroit was fiercely defended in multiple overlapping ways. Black Detroiters were mostly forcibly confined to the East Side ghetto, with a handful of small pockets of all-Black residence elsewhere in the city.

The first line of defense against the encroachment of Black people into white neighborhoods was the restrictive covenant. This was language written into the deed of a given property restricting its future use and sale. There were numerous organizing campaigns at the neighborhood level to opt all homes in the area into restrictive covenants barring sales to non-whites. Federal HOLC appraisers even gave better ratings to white neighborhoods covered by these restrictive covenants.17 Citing an early study, Sugrue writes:

In a survey of deeds for ten thousand subdivisions in Detroit, sociologist Harold Black found that racial restrictions were ubiquitous by the 1940s. More than 80 percent of property in Detroit outside of the inner city (bounded by Grand Boulevard) fell under the scope of racial restrictions. Whereas no land developed before 1910 was restricted, deeds in every subdivision developed between 1940 and 1947 specified the exclusion of blacks. A typical racial covenant stipulated that property along Seebaldt Avenue between Firwood and Beechwood Avenues on Detroit’s near Northwest Side “shall not be used or occupied by any person or persons except those of the Caucasian race. 18

This practice was undermined by the 1948 Supreme Court case Shelley v. Kraemer, which found that racially restrictive covenants could not be upheld as legally binding in US courts. These restrictive covenants did not disappear, however, and they reserved a certain moral force over home sellers and realtors. Other forms of superficially race-neutral covenant restrictions remained legally binding and were just as effective at keeping prospective Black neighbors at bay. For instance, courts would uphold restrictions on multi-family dwellings, which were the only way the vast majority of Black families were able to afford housing in Detroit. Others required neighbors or a community board to first approve a sale, or made membership in a community association a condition of residence, the bylaws of which would typically have a whites-only clause.19 These amounted to the same thing as covenants of explicit racial exclusion.

The second line of defense was the practices of the real estate industry. As Sugrue writes, “A web of interlocking real estate interests—brokers, speculators, developers, and banks—built on the base of racial animosity to perpetuate racial divisions in the housing market.”20 Professional associations of realtors closely guarded their reputations as protectors of the racial caste system and put out strict guidelines against selling homes in white neighborhoods to Black buyers. The code of ethics of the National Association of Real Estate Boards read: “a realtor should never be instrumental in introducing into a neighborhood…members of any race or nationality…whose presence will clearly be detrimental to property values in that neighborhood.”21 The Detroit Real Estate Board (DREB) pledged itself to these guidelines, and any of its members who violated them would be penalized or expelled. Using a practice called “steering,” realtors would mislead prospective Black homebuyers about which homes were on the market and direct them only to substandard housing in ghettoized Black neighborhoods even if they were able to afford better housing.

On top of all of this, any “unscrupulous” realtor (by the standards of these segregationist principles) who tried to help Black homebuyers cross the color line could be stopped in their tracks by the credit controls that banks and other lenders imposed on home loans. These too relied on the tools of red-lining developed by the HOLC to assess the “risk” of a given loan. This resulted in an unshakable institutional unwillingness to lend to Black borrowers, especially if they sought to move to a white neighborhood.22

The real estate industry did, on the other hand, pursue underhanded and highly profitable schemes at transferring white neighborhoods to Black homebuyers, which became known as “blockbusting.” The practice was fairly simple. Using a variety of tactics, realtors would convince white homeowners on a particular block that their neighborhood was on the brink of being invaded by Black families. They hired Black women from other neighborhoods to push baby strollers around the street, tricked Black homebuyers into walking around the neighborhood with fake real estate ads, and made random phone calls to homes on the block asking after someone with a stereotypically Black name. Occasionally, the real estate speculators would rent homes in these targeted neighborhoods to Black tenants to create a stronger impression that the neighborhood was in rapid descent into a slum.23

Real estate brokers would then approach these white homeowners and inform them that their neighbors were imminently planning to sell to Black homebuyers. They were told that their homes would immediately plummet in sale value, and that they should get out ahead of the “Negro invasion” and sell now. The frightened white homeowners would promptly sell their homes at below market value, abruptly emptying out an entire block. These brokers would turn around and arrange sales to Black families in desperate search of a home at wildly inflated prices, their options on the market being so artificially limited. Most Black buyers—even middle-class professionals—could not qualify for any kind of mortgage due to racist FHA policies, so the scheme of extortion continued into the future through a land contract sale. In essence, a contract sale is one in which the buyer agrees to make monthly payments over the course of fifteen or twenty years to buy the home, but accrues no equity during that time until it is paid off in full. If a single payment was made late, the seller was legally empowered to evict the buyer and return none of what they had paid up to that point. The parasitic broker would then begin the process anew with another Black family.24

While “blockbusting” entailed a violation of the color line, it is important to keep in mind that this was not in any way “desegregation” at the hands of real estate interests. Rather, they were engaging in segregation profiteering. Their practices of fear mongering about the alleged direct relationship between Black occupancy and falling home values only intensified white opposition to the integration of their neighborhoods and redirected white resistance into white flight.25

The third line of defense, for the tiny numbers of Black families who were somehow able to break through the first two, was vigilante mob violence. Black homebuyers who moved into white neighborhoods against all odds found themselves faced with relentless hatred and threats from their new neighbors. Homes were ransacked, flooded, and smashed in. In some instances, Black families were physically attacked or their homes burned to the ground by furious white mobs. In the postwar years, more than two hundred incidents of white mob violence against Black Detroiters who had crossed the residential color line were reported.26 While less lethal than the vigilante executioners of the Klan, this violent backlash was reminiscent for many Black Detroiters of the terror that they had escaped from in the South.

These campaigns of intimidation were not random acts of disorder, but tactics of a well-organized resistance movement of thousands of white Detroiters who were active in grassroots community organizations—which Sugrue characterizes as “one of the largest grassroots movements in the city’s history.”27 New Deal racial policies (and, of course, many other structures of the racial capitalist economic order) had baked anti-Blackness into the underlying political economy of housing and its related processes of capital accumulation. Race was (and, I argue, remains) a material structure of American capitalism. In this context, organized white resistance to neighborhood integration was as much about defending from perceived threats the small amount of capital that they as working people had been able to accumulate as it was about white prejudice. Indeed, the imperatives of the former fed and sustained the latter. And when Black Detroiters managed to secure a foothold in any given neighborhood, it did not result in integration. All but the poorest or most fervently progressive white residents simply moved away, either to other segregated white neighborhoods in the city or to the emerging suburbs.

Segregation created two housing markets in the city, turning housing into an even more lucrative site of capital accumulation. With the places they could live so severely restricted, Black Detroiters paid much more rent than white Detroiters for far worse housing. Sugrue estimates that Black tenants paid 20 to 40% more than white tenants for equivalent apartments.28 He cites one case of a landlord who “converted” a building from white to Black occupancy and increased rents from $25 per month to $15-$18 per week (it was common for Detroit slumlords to demand rent from Black tenants on a weekly or biweekly rather than monthly basis).29 Many slumlords illegally subdivided apartments to create new rentable units. The dangers of overcrowding were magnified by neglect of building maintenance.

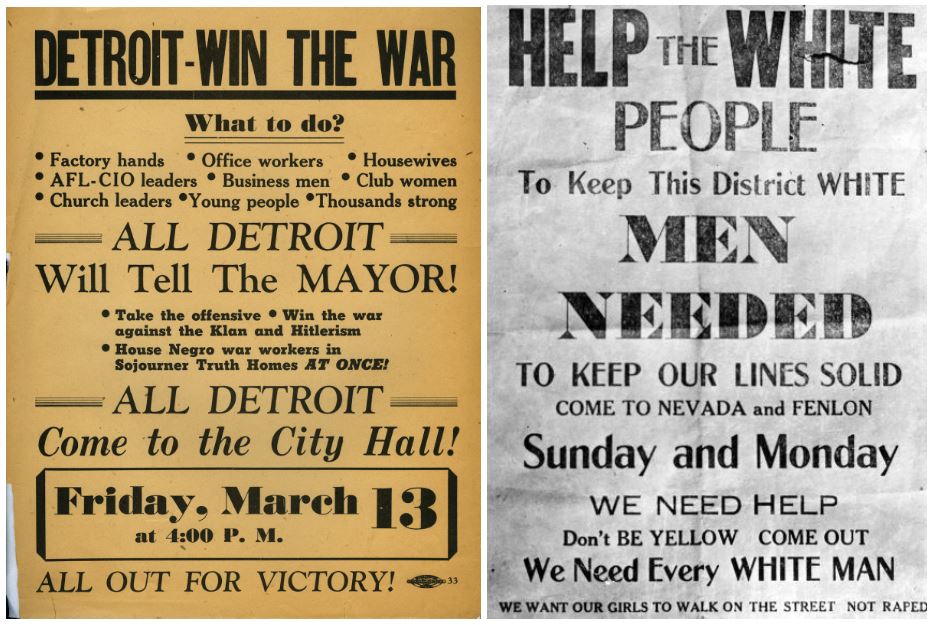

Public housing was still primarily a tool in the urban policy arsenal for responding to housing shortages. With Black people locked out of so much housing in Detroit, and with such severe overcrowding in the East Side ghetto, it was apparent to city officials that new public housing for Black Detroiters desperately needed to be constructed. As a result, local opposition to public housing projects in their neighborhoods became an additional front in the battle for “Negro exclusion.”

“Urban Renewal Means Negro Removal”: The Reign of Cobo

As far back as 1941, with the unrest around the Sojourner Truth Housing Project,30 public housing had been an explosive issue. It occupied center-stage in the political battle of the 1949 mayoral election, where UAW activist and liberal city council president George Edwards faced the city treasurer Albert Cobo, a one-time corporate executive and conservative Republican.

Edwards made his appeals through organized labor, but Cobo organized through the white neighborhood improvement associations. Cobo responded to Edwards’s twelve-point progressive platform with fear and outrage about public housing and “Negro invasion” of white neighborhoods. By tapping into the energized white neighborhood organizations and mobilizing them around their central political issue—keeping Blacks out—Cobo swept the election with 60% of the vote in a heavily Democratic and pro-union city.32

He made clear that he would wield his office to obstruct any new construction of public housing projects in white neighborhoods. This was a serious problem for addressing the housing shortage, as virtually all remaining open land in the city was in the white-dominated periphery, and the areas where Black people were already permitted to live were crammed to the brim.

Cobo was not alone among local politicians in his anti-public housing crusade. Neighboring Dearborn’s white supremacist mayor Orville Hubbard served fifteen consecutive terms (1942-1978) and militated against public housing and the possibility of Black newcomers over his entire career. At one public forum about the housing issue, he rejected the idea that it was Dearborn’s responsibility to house Black workers (many of whom were employed in Dearborn plants) from Detroit, declaring “When you remove garbage from your backyard, you don’t dump it in your neighbor’s.”33

The conditions of overcrowding in the East Side ghetto continued to worsen. Not wanting to touch the political hornet’s nest of building housing open to Blacks elsewhere in the city, Detroit housing officials looked to slum clearance: targeted demolition of Black neighborhoods with the stated goal of rebuilding safe, modern, and higher density public housing in its place. But when these demolitions moved ahead, it was the highway craze—not public housing—that topped the agenda.

Dwight Eisenhower had been inaugurated as president in 1953, and he was particularly interested in energizing federal spending on highway construction. As a young lieutenant colonel in the US Army, he had participated in the First Transcontinental Motor Convoy exercise, which sought to drive military vehicles from Washington, D.C. to San Francisco, a journey that took two months. Then during World War II, he saw firsthand the significance of German highways enabling the rapid transportation of soldiers and military equipment. As a result of these experiences, he saw a national system of highways connecting the entire country as an imperative for American military readiness in the event of an imagined Soviet invasion. The interstate highway system was also envisioned as an economic development tool. Indeed, the official report from the 1919 convoy had concluded that such a highway system was urgently needed as “a commercial asset to further colonize and develop the sparsely settled sections of the country.”34

At Eisenhower’s direction, Congress passed the National Interstate and Defense Highways Act (the name makes clear its militarist motivations) in 1956. It authorized $25 billion dollars for highway construction across the country, the largest public works project in the country’s history. In addition to connecting major cities together, these funds were also used to transform the built environment of cities, leveling commercial and residential areas to build freeways in their place.

The destruction of the city in order to make more space for the cars of the wealthy was not new in the 1950s. Large stretches of buildings along Michigan Avenue and Woodward Avenue in the center of the city were demolished to widen those roads several decades prior.35 But with federal funding footing 90% of the bill for highway construction in the 1950s onward, it was at a dramatically greater scale.36 As with public housing projects, many of the specifics of implementation were left to local planning officials. These planners were careful to avoid disrupting the neighborhoods of middle-class whites, where home values were higher and residents held more political influence. Instead, in Detroit and in cities across the country, these highway projects were aimed again and again through the heart of Black communities. Indeed, they were seen as effective tools for eradicating troublesome Black slums. This violent process was euphemistically termed “urban renewal.”

One particularly wrenching casualty of this war of bulldozers and automobiles in Detroit were the Black Bottom and Paradise Valley neighborhoods, the cultural and commercial heart of the East Side ghetto just east of downtown. Black Bottom—named not for the skin color of its residents but for the dark, rich soil the French colonists had found there—was home to an incredible density of jazz clubs and other musical institutions that raised new generations of performers whose influences on American music rippled across the country. These and all other touchstones of Black cultural life in the neighborhood were destroyed in the early 1960s for the construction of 1-375. Residents were given only a thirty-day notice to vacate, with no relocation assistance at a time when the housing market for Black Detroiters was still extremely tight. Most of the displaced were simply crammed into even more overcrowded housing within one mile of their demolished prior apartments. As other freeways criss-crossed their way across (and perhaps more to the point, through) the city, they trailed a wake of devastation. Sugrue writes,

Left behind was what one black businessman called a “no man’s land” of deterioration and abandonment. The announcement of highway projects came years before actual construction. Homeowners and shopkeepers were trapped, unable to sell property that would soon be condemned, unable to move without the money from a property sale. Building owners had no incentive to invest in improvements. An enormous number of buildings were condemned and leveled to make way for the new expressways.38

In her study of the psychological impacts of urban renewal on these displaced urban refugees, Mindy Thompson Fullilove estimates that between 1949 and 1973, approximately 2,500 neighborhoods (1,600 of them being predominantly Black) in 993 American cities were destroyed in such projects.40 While this scorched earth offensive on Black neighborhoods and the community institutions that anchored them was dressed in language of renaissance and economic progress, these were transparent falsehoods to all in the path of such destruction. One widespread slogan of rage and loss cut through this deceit: Urban Renewal Means Negro Removal.

Mayor Cobo was the city’s most enthusiastic booster of these various urban renewal expressway projects. Over the protests of displaced residents he remarked that “Sure there have been some inconveniences in building our expressways and in our slum clearance programs, but in the long run more people benefit. That’s the price of progress.”41 These new constructions, which were submerged to allow certain other streets to pass over them, were so closely tied to the public image of Mayor Cobo that they became nicknamed “Cobo’s Canyons.”

The damage to Detroit wrought by these projects was not just the demolition of buildings that lay in their path. Rather, they were essential to the overall process of urban decentralization. Built for automobiles alone and liberated from cross-traffic, this new infrastructure shrunk the distance between urban employment and residence on the suburban periphery. It became economical for thousands of car-owning, relatively affluent white workers and middle-class professionals to live outside of the city they depended on for their livelihood, and they took their taxes with them.

Physical destruction of housing in turn placed market pressures for further residential development outward. As the region began to suburbanize, more people relied on cars to commute, creating more political support for destroying ever greater swaths of the city to make way for car traffic. A dialectic of violence emerged between the mutually escalating tendencies of the decentralization of the city and the transformation of the city into a more auto-friendly landscape.

While white flight from Detroit was not yet a flood during Cobo’s time as mayor, it was under his leadership that the conditions for a mass retreat were put in place. This was a matter of more than roads. The Detroit Water and Sewerage department subsidized the expansion of new suburban communities by extending their water and sewerage infrastructure beyond the city limits. They were seeking to invest in a new customer base, but instead simply enhanced the economic viability of this peripheral development and helped funnel more white Detroit residents outside of the city. The result was an overextended water system the city struggled to pay for and maintain with its diminished population base, such that even today affluent suburbanites pay a fraction of the cost for water that Detroit residents pay to cover debts of building suburban water infrastructure.42 Another force laying the groundwork for an emptying of the city was the dispersal of employment. New roadways and highways were making it possible for industries to relocate to these new suburbs, freeing suburban residents from even the hassle of commuting back to the city. Further incentives came from the federal government’s national policy of industrial decentralization. As with the interstate highway system, this too was motivated by Cold War militarism—the US government sought to minimize the military vulnerabilities of a possible nuclear war with the Soviet Union by dispersing population and heavy industrial production from urban centers.43 Between 1947 and 1955, the three major automobile manufacturers in Detroit built twenty new plants in the suburbs.44 These processes of outward dispersal of economic growth were accompanied by economic contraction in the city itself, and brought new precarity into the lives of Black Detroiters. All of this continued into the 1960s, even with Mayor Cobo’s death and then the election of liberal Democratic mayor Jerome Cavanagh through a flood of Black political support.

By the mid-1960s, the civil rights movement had won critical victories, but a counter-revolutionary retrenchment of segregation was just around the corner. Many white people outside the South had sympathized with civil rights organizations as they fought for voting rights and access to public amenities, but these opinions soon soured when the movement turned its attention to other forms of segregation whose defeat required more direct collision with the property rights of whites. Discriminatory practices by private businesses like restaurants and motels were the first targets, finally subdued through federal civil rights legislation and subsequent court challenges. Then after 1965, civil rights organizations turned their sites northward to the thorniest problem of white property and Black exclusion of all: housing discrimination. These local civil rights campaigns for equal housing rights in the late 1960s ran into extraordinary resistance and faced deep internal divisions. They were all—without any exception that I know of—resoundingly defeated.

The problem was that whites ceased to see Black demands as pleas for equal treatment, but instead as threats to whites’ rights and freedoms. Desegregating lunch counters was opening the door to federal meddling in the decisions of private businessmen about what to do with their own property. Desegregating neighborhoods was robbing white people of their right to free association, to live alongside neighbors of their choosing. Desegregating schools was taking from parents their right to determine what learning environment was best for their child. Some wondered aloud, melodramatically, whether federal intervention into who they invited to house parties was next.

As James Ralph, Jr. writes in his history of Martin Luther King’s failed campaign for open housing in Chicago, “[The Chicago Freedom Movement] revealed the broad belief that many whites—in the North and the South—shared regarding the extent of private domain in American life, a domain that in their view deserved protection from undue public efforts to integrate. This claim underpinned opposition not only to fair-housing measures but also later to busing, one of the most turbulent issues of the 1970s.” He later continues, “Even though fair housing was a plea for equal treatment (just as the cry for access to public accommodations and for the right to vote had been), whites everywhere dismissed it as an illegitimate demand that threatened their right to basic, private decisions about the disposal of their property and, even more menacingly, threatened the quality of their neighborhoods.”45 White Americans increasingly saw the pursuit of racial integration as a source of public insertion into the private, to which segregationists offered a persuasive response: defense of the private as a means of resisting racial integration. Over the course of the 1960s, these resentful responses amassed into a national counter-revolution: one that consolidated its victories into the very built environment and political structure of metropolitan areas all across the United States, and which would transform the country’s politics forever.

In Detroit and many other Northern industrial cities, Black people remained squeezed, fleeced, and brutalized from all sides. When Black resistance to Detroit’s racial order escalated into open confrontation with that system in the late 1960s, white Detroiters already had everything they needed to abandon the city—and to erect new defensive walls behind them. The color line was on the brink of a geographic jump, but it would not soften.

“Throw in the Blankets and Corn”: Walling Off the Internal Colony

The “long, hot summer” of 1967 is often remembered as a turning point in the history of white flight. During that summer, 159 so-called “race riots” (more accurately understood as urban rebellions) rocked cities all across the country. The most violent of these was the rebellion in Detroit, and its suppression by state forces. For five days, (mostly, but not exclusively) Black Detroiters battled city police and National Guardsmen in the streets. The pressure cooker of Northern apartheid was boiling over.

Older white Detroiters have recounted to me their memories of the suddenness of white departure in the wake of the 1967 rebellion: one week the church pews full, the next half of the congregation having left never to return. In truth, white flight took place at a somewhat steadier pace. The white population of Detroit had been declining since the early 1950s, and while this decline accelerated in the late 1960s, it stretched out for many years.46 The white population of Detroit would not stabilize and begin to tick upwards again until 2014, bottoming out around 10%.

Most early white flight took place within the city, by simply retreating to another white neighborhood when they failed to keep Black residents out. Later white flight took on a new character, with the color line no longer a divider of neighborhoods but rather of independent municipalities. With suburbanization in full swing, Detroit was en route to becoming a Black city. The real turning point, then, was 1970: the year Black Detroiters became a majority of the city’s population. Three years later, Detroit elected its first Black mayor, Coleman Young.

That same year, a young attorney named L. Brooks Patterson became the county prosecutor of Oakland County, a wealthy suburban county in metro Detroit bordering the city to its north, which was at that time 96.5% white.47 Patterson had been born in Detroit, and across his long career he fought passionately to harden the barriers between Black inner city and white suburb. He had initially achieved local fame as the attorney of a white neighborhood association resisting court-ordered school desegregation in Pontiac, a small, declining industrial city at the center of Oakland County with a large Black population. This campaign against the scourge of sending white and Black children to the same schools attracted the national attention of the Klu Klux Klan and the American Nazi Party. In 1971, Klansmen dynamited ten school buses just days before the busing integration plan would go into effect.48 The case against the segregated suburban school districts of Oakland County eventually worked its way to the US Supreme Court as Milliken v. Bradley, which concluded that de facto segregation of schools (via the segregation of neighborhoods) could be distinguished from de jure segregation, such that the former was a constitutional practice, and marked the disgraceful end of court-enforced integration of public schools in the civil rights era.

Few elected officials wielded their power to halt and reverse the gains of the civil rights movement with as much fervor and aggression as Patterson. As prosecutor, he targeted welfare recipients, sex workers, and parolees, making the county as hostile as possible to the poor. In his hands the prosecutor’s office was a bully pulpit for excoriating Detroit’s underclass and attempts at cross-racial regional cooperation. He also possessed an extraordinary gift for capturing and manipulating media attention, which he had cultivated during the days of the Pontiac anti-busing campaign. Sparring matches between himself and Mayor Coleman Young played out across the headlines of the region’s newspapers, which Patterson used to articulate white suburban hostility to Detroit and its Black inhabitants. In an op-ed he declared,

If favoring the neighborhood school and opposing the attempt to make schoolchildren pawns of the federal court social experiment makes me a racist, then I plead guilty. If opposing Coleman Young’s $600 million Detroit subway, an extravagant and ineffective testament to his ego, makes me a racist, then I plead guilty… If publicly stating…that future economic bailouts for Detroit are at an end until Detroit gets its own fiscal house in order makes me a racist, then I plead guilty.49

By incorporating themselves as independent municipalities, segregationists in these new suburbs wielded powers far greater than those of their compatriots holding the line within the central city. They wrote their own zoning laws regulating land use and restricting sales to Black buyers.51 Such municipal experiments in white supremacy were well-prepared to absorb the flood of whites retreating from the urban core in the years that followed. And especially as Black voters swept their candidates into urban offices, “local control” outside the boundaries of the city became the most important defense for segregation.

Joel Batterman described this process as the unification of “the color line and the jurisdictional boundary,”52 creating a racial boundary that was inherently far more rigid than anything that had preceded it. He writes,

Detroit’s segregated suburbs dated back many decades, and the coming of the color line to Eight Mile Road culminated a long white retreat towards the city’s edge. Yet on reaching the city limits, it acquired a new political character. As Detroit gained a black mayor, a black majority, and a black identity, whites completed their retrenchment behind city and county lines which gave segregation a jurisdictional foundation.53

This era of L. Brooks Patterson was defined by a total surrender of urban space by whites, and campaigns on many fronts to separate themselves from the city as much as they could. As he viciously remarked, “What we’re gonna do is turn Detroit into an Indian reservation, where we herd all the Indians into the city, build a fence around it, and then throw in the blankets and corn.”54

Flooded with like-minded white separatists, Detroit’s suburbs experienced explosive growth. Between 1950 and 2000, Oakland County tripled in size, and Detroit’s population had shrunk by half.55 Several of these new communities are now among the wealthiest in the country, developed in parasitic relation to some of the poorest. At certain points along 8 Mile Road, the boundary between Wayne and Oakland Counties, life expectancy at birth plummets by twelve years when crossing to the Detroit side. This suburban growth was all in the form of low-density sprawling development: corporate office parks, detached subdivisions, and multi-lane highways.

Patterson preached the gospel of this ravenous model of land use. He stated on many occasions that “One man’s suburban sprawl is another man’s economic development.” He was, in a way, quite correct: sprawl by its nature is development for some, at the expense of those below them in the social hierarchy of the region. In more recent years, he championed immensely destructive (and expensive) projects like widening Interstate 75 while working to defeat and obstruct efforts at regional transit to lift Detroit from its dismal status as having the lowest per capita public transit spending of any large metro region in the United States. Although some areas of southern Oakland County underwent demographic transitions over his decades in office, he held the line at 8 Mile as a hard political boundary until his death in office in 2019.

These emerging political forces that secured newly segregated conditions across the country became the foundations of right-wing politics after the 1960s. Propertied suburbanites, carefully attuned to racial dog whistles about the dangers and inferiority of non-whites in the inner city, learned a new vocabulary for public discourse, which revolved around the rights of property owners, governmental non-interference, and distrust of public goods.56 Each of these rested on segregationist fear of non-white and specifically Black presence in what they hoped to maintain as entirely white spheres of life. This fear was closely wedded to their narrow interests as homeowners and taxpayers, which could be upheld with race-neutral language for a new era.57 Kevin Kruse terms this new conservative movement rooted in separation from the city and the public sphere “the politics of suburban secession.”58

Between the defeat of most campaigns for racial equality in housing, the election of Richard Nixon in 1968, the judicial reversal on school desegregation in the early 1970s, the dramatic migration of whites to secure residential segregation more deeply than ever before, and the ultimate triumph of suburbanite reaction over national politics through Reaganism, movements for racial equality faced a full-blown counter-revolution following their high watermark in the late 1960s. It ensured that desegregation would never be completed in the United States, and indeed rolled back many of its central achievements. The process of suburbanization consolidated this counter-revolution into the very geography and built environment of virtually every metropolitan region in the country.59 Martin Luther King, Jr. had written in 1967 that “The suburbs are white nooses around the black necks of the cities,”60 and in the decades following his murder they drew ever tighter.

To summarize, the disastrous impacts of New Deal-era and postwar federal planning policy on the lives of Black people across the country manifested in three basic ways. First, they were locked out of the wealth-building project of homeownership. Instead, they could only turn to predatory land contracts that were little better than scams or to rent-gouging slumlords who profited immensely from providing substandard housing to Black people. Second, their communities were physically destroyed to make way for the highway construction projects that were necessary for suburban white communities to be economically viable. Third, this subsidized flight of whites from the cities starved their public goods and services and set in motion new processes of uneven and combined development.62 These entangled processes are why the racial wealth gap has increased dramatically in the decades since winning formal political equality.63 Between 1983 and 2013, white household wealth increased by 14%, while Black household wealth declined by 75%.64 The entire political economy of metropolitan real estate and housing in the United States has been organized around the reciprocal processes of segregation and ecosystem destruction.

Marshland, Meadow, Farm, and Forest: Paving the Periphery

The ecological consequences of suburbanization in the United States are incalculable. We can attempt to grasp the scale of this destruction, however, by breaking it down into some distinct problems.

First and most obvious is the immediate destruction of ecosystems to make way for suburban sprawl. While different metropolitan regions experienced dispersed outward growth on different timelines, the period from 1950 to 2000 nationally was broadly characterized by major expansions in the area of land use for new low-density development that outpaced overall population growth.

The US Geological Survey carried out an extensive series of studies on land changes in different ecoregions of the country between 1973 and 2000, which provide detailed data on conversions of land from agricultural land, grasslands, forests, and wetlands to developed areas65 and other ecologically depleted uses. In the Western United States, developed land area increased by 48 percent over this period; in the Great Plains of the United States by 38.3 percent; in the Midwest-South Central United States by 42 percent; and in the Eastern United States by 26.6 percent.66 Much of the most rapacious outward growth was in regions with large Black presence in central cities, such as Chicago (total metro region population growth of 48 percent between 1950 and 1995, with developed land coverage expanded by 165 percent in that same period)67 and Michigan (home to numerous Black-majority cities, most prominently Detroit; state population grew by just 7 percent between 1980 and 2010, while developed land expanded by 50 percent).68 By the end of this period, Michigan’s land development was progressing eight times faster than its population growth.69 All of this outward growth across the country was built upon more than one million acres of destroyed forests, grasslands, and wetlands each year.

Yet the ecological consequences of turning ecosystems into parking lots extend beyond the raw numbers of land area conversions. Especially on the fringes of metro regions, this development frequently followed a leapfrog development pattern. When a given area becomes built up, the land immediately surrounding it will become more expensive, and so new developers frequently leap over vacant undeveloped land to more distant open areas where land is cheaper. This subdivision of larger natural areas into smaller, non-contiguous ones causes habitat fragmentation. Wildlife then faces serious barriers to freedom of movement, access to mates, and access to food and water, as well as exposure to new threats to their survival, such as invasive pest species, domesticated pets, pollutants, and death by motor vehicles. Habitat fragmentation is generally accompanied by population collapse that outpaces the rate of habitat loss by area, decline in population genetic diversity, and local extinctions.70

Second is the indirect destruction of ecosystems to physically build the suburbs. This massive, sustained construction boom over multiple decades unleashed a historically unprecedented demand for cheap building materials. Old growth forests were converted to billions of feet of board length during the postwar period. By the mid-1980s, timber had become the highest value crop produced in the United States, a quarter of which was harvested from national forest land in the Pacific Northwest.71

Another major industrial input for building the suburbs was concrete. Concrete is immensely destructive to produce. It consumes enormous quantities of fossil fuel energy, as some minerals essential to its production process must be heated to 1,500 degrees Celsius. It is estimated that approximately 8 percent of global carbon emissions are solely a result of concrete production.72 Concrete is also mainly composed of sand, which must be extracted in vast quantities for modern construction. Eighty-five percent of all mineral extraction on Earth is sand mining, mostly for concrete. Ocean beaches, river beds, inland dunes, and open-pit mines are the primary sources (the small, wind-smoothed grains of desert sand being useless for concrete), each resulting in different kinds of environmental destruction, including habitat loss, soil and water pollution, erosion, lowering water tables, salinization of freshwater wetlands and rivers, flooding, and drought. Sand additionally makes up 90 percent of asphalt used for road construction, and it is also used for making window glass.73

The suburban construction boom also fueled multiple related industries highly dependent on natural resource extraction, like car manufacturing, mining, and petroleum, all with a devastating environmental impact on ecosystems far from the suburbs themselves.

Third is the strangling of land with impervious surfaces. These are materials that water (such as from rainfall) cannot freely flow through, as it can through soil. Modern construction methods proliferate such surfaces in developed areas, and in low-density, auto-oriented suburbs most of all. This includes roofs for homes and other buildings, but mostly asphalt and concrete for parking lots, roads, overpasses, driveways, sidewalks, and other automobile infrastructure. Instead of flowing into the ground where pollutants will be filtered from the water, rainwater becomes runoff. Pollutants from asphalt roofs, lawn fertilizers and pesticides, motor oil, gasoline, detergents, cigarette butts, and even dog excrement are funneled by impervious surfaces in vast quantities into storm drains as well as streams and other waterways.

There are two main kinds of stormwater management systems in the United States, each with different problems for water pollution. First are separate stormwater sewers (called “MS4s,” short for “municipal separate storm sewer system”). These are systems of drains, ditches, and underground pipes that collect polluted stormwater runoff flowing over impervious systems and discharge it directly into local streams and rivers without treatment. The second are combined sewer overflows (CSOs). These collect stormwater runoff, sewage from homes and other buildings, and industrial wastewater into a single underground sewer system, which directs it to a sewage treatment plant before being released into waterways. These result in less daily pollution, but also pose their own serious risks. With so little permeable ground remaining in developed areas, any heavy rainfall can easily create overflow of these combined systems. When this happens, operators of wastewater treatment plants have little choice but to release raw human sewage and toxic industrial effluents directly into rivers. Such events poison fish and other aquatic life and pose threats to human health.

Stormwater runoff is the single greatest source of water pollution in the United States, in large part due to the land area covered in impervious surfaces (though industrial agricultural practices also play a large role). Suburban lawns and the sheer amount of freshwater, fertilizers, and herbicidal poisons needed to maintain them are a major culprit. The used oil from a single oil change in a car can pollute one million gallons of freshwater. There are no reliable figures for how much motor oil leaks onto road surfaces, but the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) estimates that “about 193 million gallons of used oil…, or roughly the equivalent of 17 Exxon Valdez oil spills” is improperly dumped by American households every year.74

Fourth is the transition from walking and use of public transit to the near-universal use of individual automobiles. Suburbanization entailed the creation of a built environment that is entirely organized around the demands of cars and actively hostile to pedestrians, bicyclists, and public transit. Residents of sprawled suburban communities spend three to four times as much time driving as those in dense urban areas. The number of cars needed by individuals to navigate suburban space only goes to strangle what makes cars convenient and luxurious. The contradictions of automobile transport therefore demand a political feedback loop of expanding car infrastructure to alleviate the road space and parking congestion created by cars. This only increases the distances between destinations, in turn increasing the time drivers must spend on the road and therefore the amount of congestion. Highway expansion projects all suffer from induced demand, where pre-expansion levels of congestion soon return. André Gorz concluded in “The Social Ideology of the Motorcar” that “[i]n the final analysis, the car wastes more time than it saves and creates more distance than it overcomes.”75

Locally, this results in worsened air pollution. All motor vehicles (especially those with diesel engines) produce nitrous oxides (NOx), which kill thousands of people every year. Other deadly pollutants include particulate matter, fine particles of soot that penetrate deeply into and damage the lungs, and volatile organic compounds (VOCs), which react with NOx to produce the ground level ozone that causes smog and damages lungs. All of these increase rates of asthma and other respiratory diseases while also making asthma more deadly. Air pollution eventually becomes water pollution, as these gases and particulate matter are dissolved in rainwater and contaminate rivers, lakes, and oceans.

For global ecological effects, the transportation sector dominated by personal vehicles is the primary greenhouse gas emitter of the economies of metropolitan areas in the United States.

Fifth is the more broadly energy intensive nature of low-density living. Car dependence is a part of this, but it extends to all aspects of providing these areas with food, energy, mobility, and consumer goods. Previous studies of carbon footprints found a simple negative inverse relationship between population density and per capita carbon footprint. The conclusion made sense: the more spread-out people are, the farther people have to go to reach destinations, the farther goods have to be transported, the more electricity lost through transmission and distribution line distance, the less viable mass transit is, etc. A more expansive 2014 study, however, concluded that suburban areas were the primary culprits, with even higher per capita carbon footprints than rural areas, to the point of actually canceling out the benefits of the urban areas they parasitically surround. Inner cities, as always, were found to have the lowest per capita carbon footprints of all.76

Suburban physical space between people, destinations, and objects of consumption is spread wide to create room for the very vehicles needed to mediate it, and to accommodate the profitability of the developer interests who built it. This spreading itself destroyed much of the local agricultural production that ringed the dense cities of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, to be replaced by truck shipping on the interstate highway system. A related element of this is that the concentration of wealth in areas where land is inexpensive means people live in larger homes that require vastly more energy to heat and cool.

With each of these dimensions of the suburban metabolism emerging together, a whole new way of life dependent on unprecedented levels of fossil fuel consumption—what Markus Wissen and Ulrich Brand termed the “imperial mode of living”77—was locked into the very built environment of these white flight communities.

Despite the immensity of its ecological consequences, there has been little discussion of suburbanization or its causes as a historical process in the social ecology literature, and what exists is sometimes misplaced in its analysis.

For instance, in his first major work, Our Synthetic Environment (1962), Murray Bookchin characterized suburbanization as weary Americans seeking refuge from “the over-all deterioration of modern urban life,” a “compelling need that is sending millions of people into the countryside” as they “vot[ed] with their feet.” The notion, of course, that suburbanization was driven through the self-direction of individual families leaving behind “the burdens of the metropolitan milieu” is simply wrong. It was the product of central planning, from the federal agencies and administrations down through municipal governments to implement top-down schemes of racist social engineering. None of this could possibly have taken place without the enormous investments of the public sphere in low-density housing construction, mortgage access, highway construction, and water and sewerage infrastructure development on the urban periphery. The racial dimension of flight from the city is elided completely—what, exactly, are the horrors of deteriorating urbanity that these affluent refugees were escaping? It was, at the end of the day, Black families moving next door.

His next book, Crisis in Our Cities, was something of a sequel to Our Synthetic Environment. It is a similarly journalistic environmental health account but focused on pollution now as a problem of specifically urban life. Bookchin’s discussion extends from the environmental concerns of smog and toxic effluents to assess the harms the modern city also inflicts on our mental and social health. His references to suburbanization here are limited but negative, and always framed as simply a feature of expansionary urban growth. He simultaneously decries the allegedly inherently stress-inducing existence of living stacked on top of each other in great densities and the churning up of peripheral agricultural areas for lower-density communities of those escaping the close quarters of the city. The city, he claims, is a good thing—to a point:

Our entire culture has emerged from the nourishing contact of thousands of people in a moderate-sized community. To fragment the human community, to scatter the thousands over the countryside, or to diminish the contact provided by an urban arena would result in a social barbarism as devastating to the human spirit as congestion and pollution are to the human body.79

Yet note the importance of the words “moderate sized”—the argument of the book is that urbanization has gone too far, that the problems of pollution and employment-related stress are attributable to the increasing size and density of modern cities (rather than to, say, capitalism), which must be “arrested by firm social action.”80 This growth of urban areas is described as an “epidemic,” first to be “contained by drastic quarantine measures” until its causes can be “identified and removed by lasting control measures.”81 He writes longingly of a future where “urban communities are reduced in size and widely dispersed over the land.”82

Most concerningly, this extraordinarily detailed overview of runaway city life as “an incomprehensible and possibly uncontrollable force”83 in the mid-1960s makes zero reference to race or racism as an element of the “urban crisis.”84 I hope my own historical account of these changes makes clear how significant an oversight this was.

Fortunately, Bookchin later offered some corrective to the depoliticized narrative about suburbanization and the American city that appears in Our Synthetic Environment and Crisis in Our Cities. Discussing exurbia in 1974, he writes,

To the inhabitants of “spread city,” New York is an object of active hostility. Although they depend upon the city for their means of life, they are oblivious to its civic problems, impatient with its inconveniences, disloyal to its political interests, and desperately fearful of its encroachment on their enclaves. They are New Yorkers in fact and depend upon the city for their well-being, but their hatred of New York is as parochial and chauvinistic as the hostility that the rural dweller feels toward all large cities. Divorced by residence from the tax base that supports the city’s essential services, they provide only a minimal contribution to its revenues. The bad conscience they—and suburbanites generally—feel toward the city finds a perverted expression in the representatives they send to the state legislature: reactionaries who are responsible for the most vindictive measures against New York… They are strangers to this city not only because of their active disloyalty to its interests but, perhaps most significantly, because of their oblivion to its agony. The commuter trains, buses, and automobiles that swoop past New York’s proliferating ghettoes are enclaves of an alien culture that is in mutual war with the urban environment. To the ghetto dweller, these conveyances are not means of transportation, nor are the people who occupy them mere strangers; they are the self-enclosed strangers as enemies… The vehicle that conveys the suburbanite and exurbanite into the city is not a cultural enclave, but a fortress.85

In Urbanization Without Cities, he describes the city’s “complete dominance over the countryside…with the extension of suburbs into nearby open land on an unprecedented scale…literally engulfing the agrarian and natural worlds.”86 Zeroing in on the environmental dimensions of suburbanization in her essay “Suburbia as an Ecological Problem”, Janet Biehl similarly writes,

Far too much of the country’s built environment is auto-dependent: more than half the population live in sprawling suburbs, a landscape that requires every adult living in every household to have a car in order to function. The social and ecological problems generated by sprawl are well known. Above all, suburban lifestyles are environmentally unsustainable: they spew higher emissions than urban ones, due to their dependency on the automobile for every trip outside the home. The single-family homes lack the energy efficiency of multiple unit buildings. And low-density settlement pattern renders suburbia unable to support public transit. The long distances between destinations, and inadequate sidewalks, disqualify walking as a mode of transportation. Pedestrians who wish to cross an intersection on an arterial connecting enclaves risk their lives, darting across a yawning chasm in brief pauses in traffic. Schools are no longer an easy walk from home: back in 1969, about half (49 percent) of grade-school children walked or bicycled to school, but only 13 percent did in 2009. Parents now routinely drive children to play dates instead of letting them walk. In some suburbs children aren’t allowed to play on sidewalks. The result has been an epidemic of obesity—children today have a one in three chance of getting diabetes.87

These recognitions of the social and ecological violence of suburbanization aside, however, elsewhere Bookchin continued to hold up the goal of “physical decentralization” of our cities as socially and ecologically desirable transformations—in essence, depopulating urban cores so that smaller human communities can be distributed more widely.88 A small town intentionally constructed to be communally oriented is by no means the same thing as a suburb, and yet this prescription still simply flies in the face of ecological reality for many of the same reasons. As we desperately fight for solutions to the climate crisis, it is immensely important that social ecologists set aside and counter the anti-urban sensibility that has characterized so much American environmental thought.89

The Walled Commons to the Picket Fence

In the several decades before mass suburbanization, local governments all across the country invested handsomely in public swimming pools. They embodied an ethic that recreation could be a public luxury, even (or perhaps especially) in crowded, working-class cities.

Almost every public swimming pool in the country was also segregated. In some cities, Black people were only allowed to use a small indoor pool and banned entirely from the large ones that whites frequented. In others, there were special time slots during the week where Black people were allowed to get in the water. One older Detroit resident told me about his uncle, one of the few Black competitive swimmers in the city at that time, for whom swim meet officials would drain and refill the entire pool each time he got out of the water from a race. Whites often explained these absurd and humiliating exercises as “precautions” against the various skin diseases that Black people were imagined to carry. Even outside the South, many white people felt a visceral disgust at the thought of races mingling in the intimate space of a swimming pool.